My second book, All the Ways We Kill and Die, was this book. “Gladwell on IEDs” or “Gladwell on Modern War.” This was the editorial feedback. Meaning, crush the narrative inside a big unifying theme that obliterates nuance but provides more reader satisfaction, that simplifies reality into an easily digestible 220-page pill with a plain white cover.

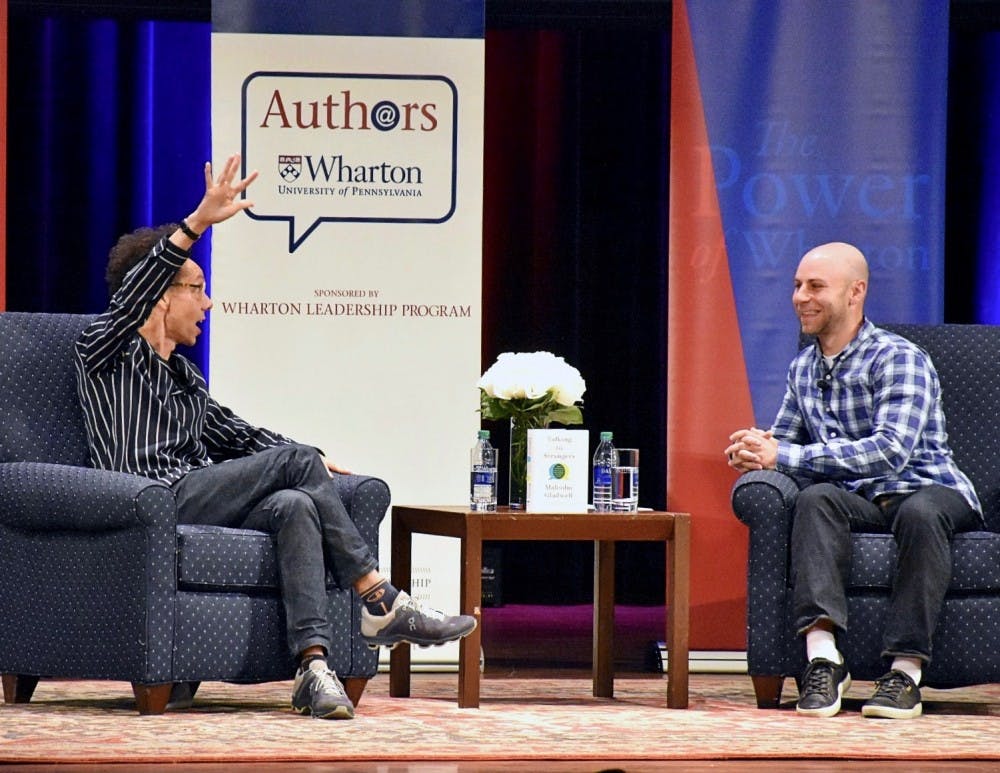

Or, more specifically, I had a book proposal that several editors said would be more successful as a Gladwell book. Which is surprising, because if anyone should be able to understand amoral perfectionists, it’s a wanna-be Tech Bro like Gladwell.īefore I go further, a relevant admission: I tried to write a Gladwell book once. My conclusion is this: Gladwell is right about Air Force pilots being obsessives, but completely wrong about the object of their desire. But as a former Air Force officer, I know a fair bit about the service’s history and culture, and so I was curious what would happen when he took on a subject I knew.

I am not a sociologist or a sports psychologist, so I can’t tell you the failures in Gladwell’s arguments in Outliers. Why one poor boy in the tenement and not his friend? Why one hockey player born in January and not another? One gets the sense that the answer may undermine Gladwell’s thesis and so is left out, or, more conspiratorially, is revealing of other Big Ideas that Gladwell has less interest in exposing, such as the false meritocracy. And even if you accept his case for why Jewish people from the Garment District born in the 1930s were destined to become highly successful attorneys, he never explains how the individuals themselves did it. Gladwell calls Outliers a how-to guide, but always dissatisfyingly so.

#MALCOLM GLADWELL HARD DECISIONS PROFESSIONAL#

Why are rich New York corporate take-over lawyers Jewish? Why are 40% of professional hockey players born in January? ( They’re not.) The book stuck with me because I had a young son obsessed with hockey should he just “give up” because he wasn’t born in the right month? My first encounter with him was Outliers, which in classic Gladwell fashion promises to explain sociological events with a surprising counter-intuitive twist. Turn the page on Gladwell-the self-proclaimed reviser of history, who helps us see and understand the overlooked and misunderstood-and what do you find? It wasn’t until he wandered into my area of expertise that I appreciated the extent of the shallowness, so to speak. You turn the page, and forget what you know.” In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward-reversing cause and effect. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. “You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well.

You know the phenomenon, if not the name.

The Bomber Mafia was my first chance to experience the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect with Gladwell. Which I think we can all agree, if nothing else, is a completely bizarre way to open and frame a book about killing millions of people with air strikes. The Bomber Mafia is not so different than his other books, he says, because it is about “obsessives,” “my kind of people.” The topic is no less than “one of the grandest obsessions of the twentieth century.” Join him, for “I don’t think we get progress or innovation or joy or beauty without obsessives.” It’s an obvious question that Gladwell addresses in the opening Author’s Note. Why did Malcolm Gladwell write a World War II book? The bombing campaign over Europe and Japan is hardly his typical beat: Cliff-noting TED talks for the MBA crowd.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)